When your past inhibits progress

or, the enduring impact that our families have on our professional identities

Real talk: I feel like I’m juggling a million balls right now and need a week to regroup. In an effort to set some boundaries and recharge, I’m going to take next week off from the newsletter. If you’re feeling overwhelmed too, I encourage you to do the same. See you October 20!

We are all, to some extent, the sum of our previous experiences. That’s not to say that our past is deterministic, but it does shape us. Today, I want to talk about the influence that our families of origin have on our adult identities, particularly our professional identities.

One of the biggest distinctions about coaching as opposed to therapy, is that therapy is often focused on processing past events, while coaching is focused on the future. One of the benefits of working with a coach who has therapeutic training is her appreciation and ability to facilitate discussions on the past when it’s appropriate.

Sometimes, in my coaching with working parents, it’s important to explore long-held mental models about work and parenthood. Mental models are the conscious and unconscious beliefs and ideas—that we all hold—based on, or in reaction to, our past experiences.

Sometimes these mental models are positive and motivating. Maybe you get your dedication and determination from your hard-working mom. Maybe your dad was a strong role model for the kind of working parent that you want to be. Other times, these frameworks can get in our way. In these cases, unearthing and examining these beliefs is essential to changing them.

To illustrate…

Jack grew up poor. Although his single mom consistently worked two or three jobs, money was always a struggle. He saw his full scholarship to an elite college as a lifeline—not only for himself, but for his mother and younger brother, too. Since graduation, he’s worked at a large financial firm. It was fine for the first several years, but now that he’s a dad, he finds that the organizational culture isn’t a good fit for the lifestyle he desires. He recognizes that he’s increasingly unhappy, but consistency and financial stability are two of his core values. He feels it would be irresponsible to quit.

Sunita has a fraught relationship with her role as a working mom. On one hand, her immigrant parents expected her to excel in school and end up in a high-paying career. On the other hand, her mother set an example as a quintessential homemaker—always making elaborate meals, planning holidays, and volunteering at her school.

Despite her incredibly busy job as a partner at a law firm, she feels tremendous pressure to go above-and-beyond at home, often at great sacrifice to herself and her own needs. She’s exhausted and burnt out, but giving less to either her job or her family would make her feel like a failure. And the one message her parents always emphasized was that “failure is not an option”.

Kate always had a hard time advocating for herself at work. She would often agree to extra (and uncompensated) work or let irritating comments slide, because she feared being viewed as “difficult” or “demanding” . When she reflected on the roots of this pattern, she realized that this was the example her father set. He would often talk about how his ability to stay under the radar was the key to his success. She internalized this message, but now found that it was standing in her way. Not only was she resentful, but her boss recently told her that he didn’t think she had the executive presence required for the next promotion.

When the past gets in our way

I sometimes find that clients can get stuck when they have mental models that are oversimplified, too rigid, or incomplete (we all hold mental models that fall into these categories—it’s not a judgement or a weakness, it’s just reality).

Because it can be so challenging to get out of our own heads, it’s often helpful to change our point of reference. One of the questions I sometimes ask clients to consider is: “If your adult child approached you with this dilemma 30 years from now, what advice would you give to him/her?”

For Jack, he was clear that he would never want his daughter to be miserable solely for the sake of a paycheck. When he spoke this out loud, he realized that he wasn’t setting an example that he wanted his own child to follow. He still wanted to stay at his organization, but felt empowered to have a conversation with his boss about increased work/life balance.

Sunita had a similar light bulb moment. She was adamant that she didn’t want her kids to feel crippled by perfectionism in the way that she did. She realized that in modeling “flawlessness” and shoving aside her own needs, she was setting her kids up to repeat the same miserable cycle she was in. For her, it was incredibly freeing to realize that being perfect was not only impossible, but also undesirable.

Kate realized that while the pushover mentality might have worked for her dad, it was clearly not working for her. She prides herself on teaching her kids to be strong advocates for themselves and was embarrassed to see that she wasn't walking the walk herself. With this new-found clarity, she felt empowered to change her mindset moving forward.

“Good ancestors”

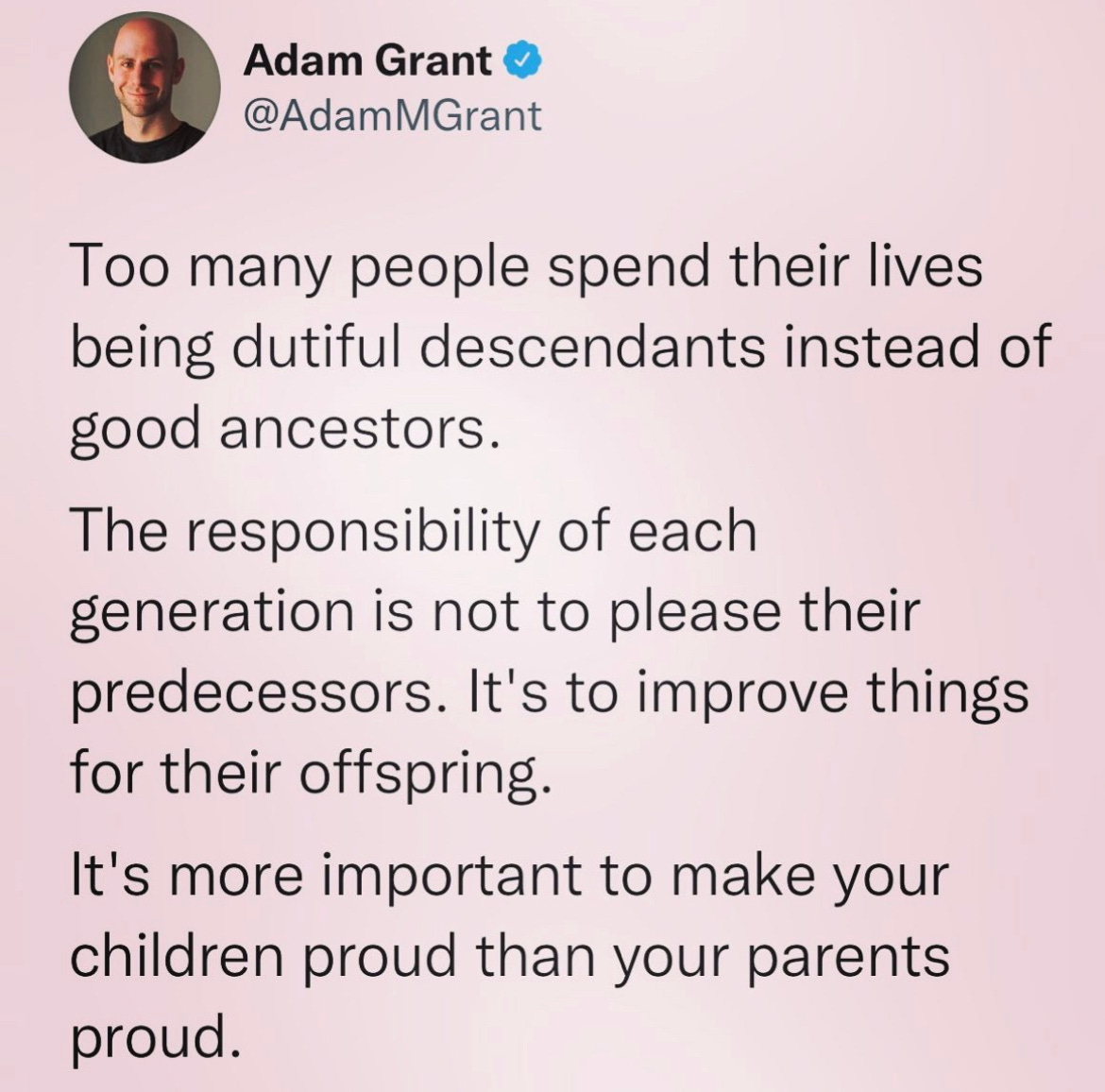

I’m not the only person to point this out. As I was drafting this article, a friend posted this quote from Adam Grant:

Sit with that for a moment. And then consider the following:

What are the values, actions, and behaviors you most want to model for your kids?

Are there areas of your life where your values/desired behaviors feel in conflict with the decisions you’re making?

Are there areas of your life where you have seemingly competing values? (For example, Jack’s tension of stability vs. happiness). Is there a way to reconcile these values and have them co-exist?

Do you hold any mental models that you want to expand, challenge, or add nuance to?

How can you honor the influence and lessons from your parents while forging your own path?

A Cup of Ambition is a weekly newsletter filled with thought-provoking essays, interviews, links, and reflections on all things related to working motherhood. If you are here because someone shared this with you, I hope you’ll subscribe by clicking on the button below.

as a child of immigrants I feel this so hard. The expectations are enormous. Thanks for writing and sharing an actionable solution about mental framework to work through it.

I love that quote from Adam Grant and I've posted it on my social media at least once, maybe twice recently.

I'm an academic who had a mom who stayed home. My dad is a church worker and therefore money was always a struggle. I'm constantly in search of financial stability (which should be "easy" with my husband and I making decent pay but life happens) and trying to be everything my family need to be. This whole piece really hits home.