I had a call this week with a health system executive who wanted some advice. His physicians (several of whom were working parents) were asking for greater flexibility. More specifically, they wanted to work from home when they weren’t actively seeing patients. This kind of request may seem unremarkable, but within the historically rigid culture of academic medicine—where presenteeism and workaholism are often worn as badges of pride—he viewed it as fairly radical.

Of course, these doctors aren’t alone. A recent survey1 found that flexibility is a major determinant of job satisfaction (second only to compensation). Employees want control over when and where they work. The 9-5 workplace no longer resonates with the majority of workers.

The pandemic has proven that most so-called “knowledge workers” can work outside of the normal office structure and still be effective, so now is a prime opportunity to reconsider traditional assumptions about the workplace and ask some tough questions. Let’s jump in…

Who does the office serve? Who is left out?

A few weeks ago, Reshma Saujani published an article in TIME with the provocative (and accurate) title: “No One Wants to Go Back to the Office As Much As White Men”. In it, she argues:

The office—in the traditional, Mad Men sense–was designed to be the workplace of breadwinners: a place where men pulled in the money while their wives stayed home doing all the work to maintain their home and family (for free, obviously). It was the American postwar iteration of separate spheres ideology, the era’s way of giving men comfortable distance from their needy, messy, somehow-always-sticky kids. And like sweet potato puree on a working mom’s blazer, it’s stuck around.

It’s true—the vast majority of office cultures privilege the “ideal worker”: an outgoing, able-bodied (often male, often white) employee with limited commitments or responsibilities outside work. For people who don’t conform to this identity, the office can feel exhausting, aggravating, or isolating.

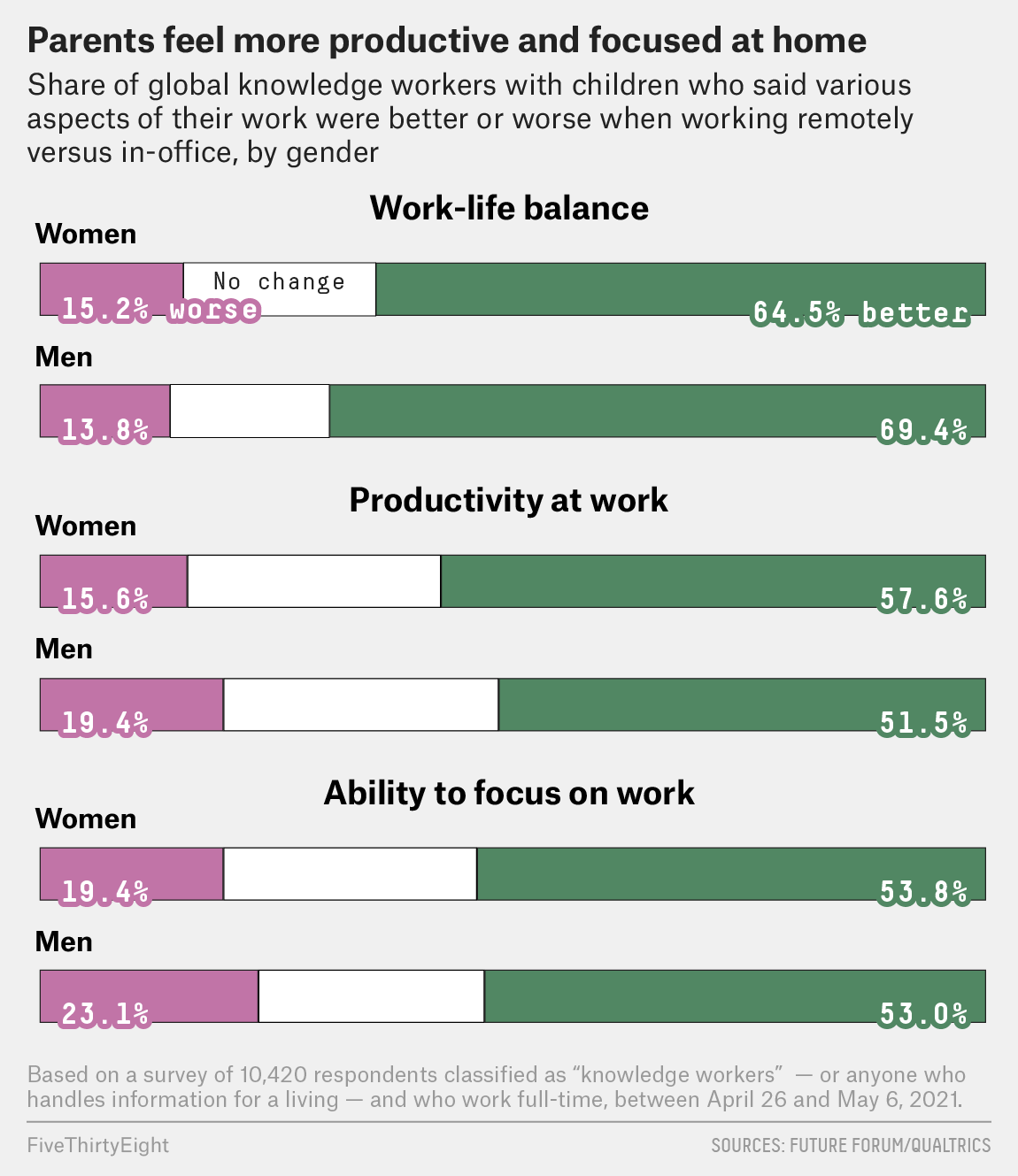

On top of that, working from home provides practical benefits. When I asked readers to share the biggest benefits of working from home, there were clear themes: more time with family and greater flexibility, autonomy, efficiency, and focus. Whatever the reason, it’s clear that most working moms don’t want to return to the office full-time (in my informal Instagram poll, precisely 0% of respondents wanted to return to the office 5 days a week).

Why are executives so committed to keeping things status quo?

But it’s not just the Don Drapers of the world itching to get back to their three martini lunches. Three-quarters of executives want to return to working in the office 3-5 days per week, compared to only one third of employees2.

Meanwhile, companies are doubling down on investing in office infrastructure. Google spent $7 billion on new office buildings in 2021, and Meta—the company formerly known as Facebook—is in the middle of building its own village (🤯) in Menlo Park with 1.25 million square feet of office space. There are several factors driving this disconnect, but I want to highlight three.

Genuine belief in the value of the office

As discussed above, traditional office settings work for a certain kind of employee—and clearly these settings have worked for those individuals who have made it to the top. I’ve seen some of these (usually older male) executives so anxious to return to pre-pandemic work norms that they genuinely can’t understand why everyone else isn’t itching to head back in the office.

Concerns about company culture

Perhaps the most frequently cited argument in opposition to remote work is the potential impact on company culture. Executives worry how to transmit their organizational values without the rituals, symbols, and environmental cues that accompany being together in a shared physical space. In short, organizations fear losing their identity.

This concern begs a larger question: Is preserving company culture a good thing? Of course, the answer depends on the company and which aspects of their culture we’re talking about. But it’s crucially important to note that rates of belonging, defined as “the sense of being accepted and included by those around you3”, have increased for underrepresented groups since the start of the pandemic4. For some employees, the physical distance of remote work provides a longed-for protective barrier.

Loss of control over workers

A more nefarious explanation is that full-time, in-office work allows supervisors to keep a closer eye on employee productivity. Of course, we all know that being present doesn’t equate to actually working. I know I’m not the only one who has spent an afternoon checking my email or online shopping waiting for 5:00 to roll around. Wouldn’t that time be better spent doing… well, almost anything else?

The idea that workers should be spending 8 hours a day tethered to their desk is counterproductive. And using face time as a correlate of employee productivity is both antiquated and misguided. There is a significant body of research that shows the employees are more productive, creative, and when they work from home (see here, here, and here).

What can offices offer going forward?

Most experts agree that the future of knowledge work is remote. However, I do think there may still be a role for offices, albeit a much smaller one.

Of course, there will always be some types of work that are truly best accomplished in person, like onboarding new employees, collaborative projects, and informal networking. As Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmundson puts it:

Working from home works best for relatively independent tasks, when knowledge is codified and can be easily shared from a distance. Being together matters when tasks are interdependent, require sharing tacit knowledge in fluid ways, and coordination needs are not scripted or predictable.

But I think the real benefit of in-person work is the potential it provides for relationship-building. Instead of thinking of offices as places where “work gets done”, we should begin conceptualizing them as places where “relationships get nurtured”.

Decades of research tells us that relationships are important for work satisfaction (and general life satisfaction too). Employees with strong ties to other people in their organizations are less likely to leave5. This presents a legitimate dilemma, since researchers6 have found that it’s more difficult for people to establish meaningful relationships when they primarily communicate in a virtual space where it’s harder to read nonverbal cues and listen intently.

Moving forward, employers would be well-suited to think intentionally about how to implement relationship-based office time. Some work may be better suited to weekly, in-person touch-points while other companies may find that monthly, quarterly, or even annual gatherings are sufficient. The key, as always, is to solicit regular feedback from employees to understand their needs for both in-office and remote work, and course-correct as needed.

I want to cover what’s important to YOU. I welcome reader input in deciding what and who to write about. Email me at drjessicawilen@gmail.com and put “newsletter idea” in the subject.

https://futureforum.com/2021/06/15/future-forum-pulse/

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/08/return-to-office-why-executives-are-eager-for-workers-to-come-back.html

https://hbr.org/2019/12/the-value-of-belonging-at-work

https://www.wellandgood.com/working-from-home-belonging-black-latinx-asian/

https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/employee-relations/pages/workplace-friendships.aspx

https://foster.uw.edu/research-brief/work-relationships-hard-build-zoom-unless-pick-colleagues-nonverbal-cues/

Ugh, Jessica, you absolutely nailed this. There are a lot of things I could say about my organization right now, but won't, just: everything in this post rings true for me, I wish with all my heart that I could go into the office three days a week and wfh the other two, this will never happen with the current (older white male) CEO. I'll leave it at that.

Thank you for calling attention to this issue.

Have had this queued up and finally had a chance to read it. It's really terrific and I'll be passing it on to others. I worked in a traditional office until 2009, then remote at least half the time until 2011 and was tremendously productive because I didn't have all of the "face to face" interruptions. A new boss (older white female) insisted I be in the office five days a week because she didn't trust that I was working a strict 9-5 day. Predictably, productivity went into a sinkhole.

Now, as a freelancer, I occasionally miss the interaction you have with people in the office, but not enough to ever go back to one. Ironically, my wife's office went virtual seven years ago, with everyone gathering in person every month to six weeks. When the pandemic hit, they didn't miss a beat. They have people working for them from all over the country, and now they can look for the best person for a position rather than settling for someone who lives in the area.